Shanghai

Why Go?

You can’t see the Great Wall from space, but you’d have a job missing Shànghǎi (上海). One of the country’s largest and most vibrant cities, Shànghǎi somehow typifies modern China while being unlike anywhere else in the land. Shànghǎi is real China, but – rather like Hong Kong or Macau – just not the China you had in mind. This is a city of action, not ideas. You won’t spot many Buddhist monks contemplating the dharma, oddball bohemians or wild-haired poets handing out flyers, but skyscrapers will form before your eyes. Shànghǎi best serves as an epilogue to your China experience: submit to its debutante charms after you’ve had your fill of dusty imperial palaces and bumpy 10-hour bus rides. From nonstop shopping to skyscraper-hopping to bullet-fast Maglev trains and glamorous cocktails – this is Shànghǎi.

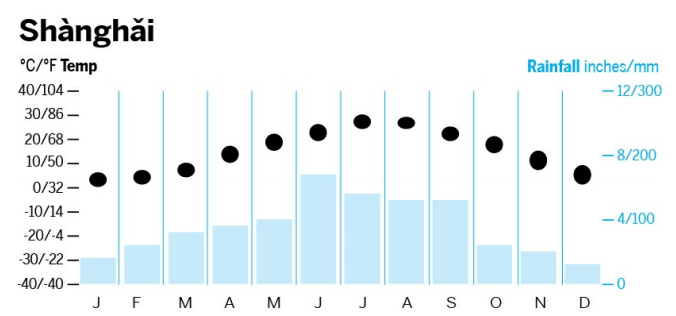

When to Go

Summer is peak season but it’s hot and sticky with heavy rain; spring and late September to October are optimal (neither too hot nor rainy). Winter is cold and clammy.

History

As the gateway to the Yangzi River (Cháng Jiāng), Shànghǎi (the name means ‘by the sea’) has long been an ideal trading port. However, although it supported as many as 50,000 residents by the late 17th century, it wasn’t until after the British opened their concession here in 1842 that modern Shànghǎi really came into being. The British presence in Shànghǎi was soon followed by the French and Americans, and by 1853 Shànghǎi had overtaken all other Chinese ports. Built on the trade of opium, silk and tea, the city also lured the world’s great houses of finance, which erected grand palaces of plenty. Shànghǎi also became a byword for exploitation and vice; its countless opium dens, gambling joints and brothels managed by gangs were at the heart of Shànghǎi life. Guarding it all were the American, French and Italian marines, British Tommies and Japanese bluejackets. After Chiang Kaishek’s coup against the communists in 1927, the Kuomintang cooperated with the foreign police and the Shànghǎi gangs, and with Chinese and foreign factory owners, to suppress labour unrest. Exploited in workhouse conditions, crippled by hunger and poverty, sold into slavery, excluded from the high life and the parks created by the foreigners, the poor of Shànghǎi had a voracious appetite for radical opinion. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was formed here in 1921 and, after numerous setbacks, ‘liberated’ the city in 1949. The communists eradicated the slums, rehabilitated the city’s hundreds of thousands of opium addicts, and eliminated child and slave labour. These were staggering achievements; but when the decadence went, so did the splendour. Shànghǎi became a colourless factory town and political hotbed, and was the power base of the infamous Gang of Four during the Cultural Revolution. Shànghǎi’s long slumber came to an abrupt end in 1990, with the announcement of plans to develop Pǔdōng, on the eastern side of the Huángpǔ River. Since then Shànghǎi’s burgeoning economy, leadership and intrinsic self675 confidence have put it miles ahead of other Chinese cities. Its bright lights and opportunities have branded Shànghǎi a Mecca for Chinese (and foreign) economic migrants. In 2010, 3600 people were squeezed into every square kilometre, compared with 2588 per sq km in 2000 and by 2014, the city’s population had leaped to a staggering 24 million. Over nine million migrants make Shànghǎi home, colouring the local complexion with a jumble of dialects, outlooks, lifestyles and cuisines.