Beijing

Why Go?

Inextricably linked to past glories (and calamities) yet hurtling towards a powercharged future, Běijīng (北京), one of history’s great cities, is as complex as it is compelling. Few places on earth can match the extraordinary historical panorama on display here – there are six Unesco World Heritage Sites in this city alone, just one less than the whole of Egypt. But this is also where China’s future is being shaped: Běijīng is the country’s political nerve centre, a business powerhouse and the heartbeat of China’s rapidly evolving cultural scene. Yet for all its gusto, Běijīng dispenses with the persistent pace of Shànghǎi or Hong Kong. The remains of its historic hútòng (alleyways) still exude a unique village-within-a-city vibe, and it’s in these most charming of neighbourhoods that locals shift down a gear and find time to sit out front, play chess and watch the world go by

When to Go

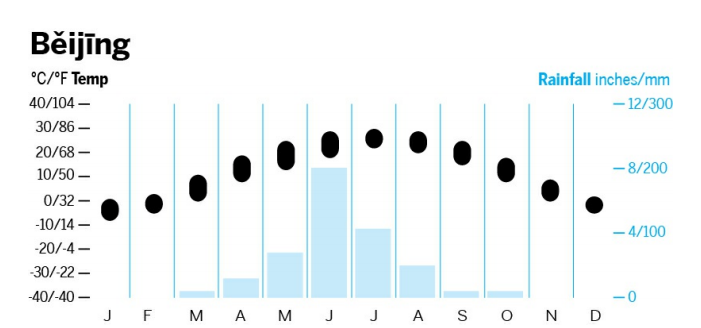

Apr–May & Oct–Nov Most pleasant.

Dec–Feb Dry and very cold.

Jun–Sep Peak season; very hot but rainstorms offer respite.

History

Although seeming to have presided over China since time immemorial, Běijīng (literally, 'Northern Capital') – positioned outside the central heartland of Chinese civilisation – only emerged as a cultural and political force that would shape the destiny of China with the 13th-century Mongol occupation of China. Chinese historical sources identify the earliest settlements in these parts from 1045 BC. In later centuries Běijīng was successively occupied by foreign forces: it was established as an auxiliary capital under the Khitan, nomadic Mongolic people who formed China’s Liao dynasty (AD 907–1125). Later the Jurchens, Tungusic people originally from the Siberian region, turned the city into their Jin dynasty capital (1115–1234), during which time it was enclosed within fortified walls, accessed by eight gates. But in 1215 the army of the great Mongol warrior Genghis Khan razed Běijīng, an event that was paradoxically to mark the city’s transformation into a powerful national capital. Apart from the first 53 years of the Ming dynasty and 21 years of Nationalist rule in the 20th century, it has enjoyed this status to the present day. The city came to be called Dàdū (大都; Great Capital), also assuming the Mongol name Khanbalik (the Khan’s town). By 1279, under the rule of Kublai Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan, Dàdū was the capital of the largest empire the world has ever known. The basic grid of present-day Běijīng was laid during the Ming dynasty, and Emperor Yongle (r 1403–24) is credited with being the true architect of the modern city. Much of Běijīng’s grandest architecture, such as the Forbidden City and the iconic Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests in the Temple of Heaven Park, date from his reign. The Manchus, who invaded China in the 17th century to establish the Qing 173 dynasty, essentially preserved Běijīng’s form. In the last 120 years of the Qing dynasty, though, Běijīng was subjected to power struggles, invasions and ensuing chaos. The list is long: the Anglo-French troops who in 1860 burnt the Old Summer Palace to the ground; the corrupt regime of Empress Dowager Cixi; the catastrophic Boxer Rebellion; the Japanese occupation of 1937; and the Nationalists. Each and every period left its undeniable mark, although the shape and symmetry of Běijīng was maintained. Modern Běijīng came of age when, in January 1949, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) entered the city. On 1 October of that year Mao Zedong proclaimed a ‘People’s Republic’ from the Gate of Heavenly Peace to an audience of some 500,000 citizens. Like the emperors before them, the communists significantly altered the face of Běijīng. The páilóu (decorative archways) were destroyed and city blocks pulverised to widen major boulevards. From 1950 to 1952, the city’s magnificent outer walls were levelled in the interests of traffic circulation. Soviet experts and technicians poured in, bringing their own Stalinesque touches. The past quarter of a century has transformed Běijīng into a modern city, with skyscrapers, shopping malls and an ever-expanding subway system. The once flat skyline is now crenellated with vast apartment blocks and office buildings. Recent years have also seen a convincing beautification of Běijīng, from a toneless and unkempt city to a greener, cleaner and more pleasant place, albeit one heavily affected by ever-increasing pollution. Sadly, as Běijīng continues to evolve, it is slowly shedding its links to the past. More than 4 million sq metres of old hútòng courtyards have been demolished since 1990; around 40% of the total area of the city centre. Preservation campaign groups have their work cut out to save what’s left.

Language

Fewer people than you think speak English in Běijīng, and most people speak none at all (taxi drivers, for example). However, many people who work in the tourist industry do speak at least some English (particularly in hotels and hostels), so, as a tourist, you'll be able to get by without speaking Chinese. That said, you'll enrich your experience here hugely, and gain the respect of the locals, if you make a stab at learning some Chinese before you come.